EN Commitment_01

Christine Nöstlinger on Christine Nöstlinger and the saying that many regard her as a moral authority:

“I'm sorry, I can’t do anything about it. And I don't even know when that happened. Forty years ago, I was considered an immoral authority.”

Taking children seriously

“A child has good reasons for everything it does, no matter how absurd and irrational it may seem to us adults! And let us admit, to start with, that we understand nothing of these good reasons.

About so many things in life we say: I don't know anything about that, I'd rather not touch it!

So let us also not touch the children who we do not understand! The insight not to understand could, over time, lead to curiosity and willingness to learn. Let's just watch and listen to the kids while they are living. They anyway try, with all their strength, to make us familiar with their way of thinking. They invent stories for us, they play them for us, they tirelessly try to provide us with insights about their thoughts and feelings.

If we were to make only a tenth of the effort that children make towards us, it would be possible to get at least so much insight that we were not constantly violating their interests and we protected them from harm.”

Source: Jeder hat seine Geschichte, Vorlesung an der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt,1992, Seite 17

Taking children seriously Part2

A manifesto of empathy. Much more well-known and quoted than this passage from the 1992 speech, was a sentence later expressed by Christine: “I am not particularly fond of children.”

Many found it ambivalent that out of all people, a well-known children's book author, would make such a statement. Christine, however, added something else:

“I'm not particularly fond of children. I am fond of humans.“

Willkommen Österreich, 29.10.2013

Taking children seriously text2

For Christine, children were primarily people who, like everyone else, have the right to be treated humane. Adults or children, women or men, ethnic Austrians or migrants – she believed that everyone should be treated with the same respect and curiosity.

A “tenth of the effort” which she demanded from adults towards children in her 1992 speech, she also demanded from natives towards immigrants, from higher classes towards the poor, from men towards women.

In Christine's worldview, empathy was by no means a moral category only, but a political one.

EN engagement_04_menschenrechte

In her interviews, articles and speeches one can feel how important human rights and the values of the Enlightenment were to her, which she also explicitly stated (when answering the question: “Where have you found comfort – in the church?”):

“I feel very distant from the Church. The values I hold sacred have been with us since the Enlightenment. To me, they’re sufficient.”

Source: Der Tagesspiegel, 27.01.2013

“...it's not only about justice, but above all about solidarity. It’s about a request for empathy and that one can empathise with strangers.“

Her political commitment, her works and her statements towards children and children's literature in general are to be understood in this context.

No pedagogical pills

Christine never tried to raise children with her books. In fact, she was convinced that the educational norms of adults had no place in children's books or pedagogy.

“If I were asked for parenting advice, I would reject that. I'm a writer, not an educator.“

EN engagement_05 Gutachter

When Christine started to write, most adults involved in children's literature felt that it was the “educational content” of a book that determined its quality.

Her first books were received badly:

“Children's books were not 'discussed' in the same way as adult literature, but 'examined' for their pedagogical suitability. And finally, ranked on a scale from 'highly recommendable' to 'rejected'. The reviewers were usually teachers and librarians.

Sometimes, this resulted in hilarious delights. A librarian, wrote succinctly about my booklet – in which the dad-butcher drinks a mug of beer for breakfast every day: 'This book is to be rejected because beer is being consumed’.

And than, all the pages were listed on which the butcher lifts his mug.“

No pedagogical pills Part 3

Christine – as many authors in the 1970s – did not want to write books that resembled “educational pills wrapped in entertainment paper”, as she frequently described them. Unconventional children's books should call for a rebellion against the authoritarian world.

Later on, Christine said that her view about what was reasonable for children to cope with (in books and in life) had changed over the years. However, her belief that children should be restricted as little as possible never changed.

“I also hate when people continuously state: “You have to set limits”, when talking about children. Unavoidably, children have to cope with many limits: they have to attend school, they have to swallow medicine when they are ill, they have to deal with the economic situation of their parents. To set additional limits is not necessary.“

Source: Ich bin in der Wolle rot gefärbt, Profil, 7.8.2010

This statement should, once again, not be interpreted as a pedagogical advice. According to her humanistic and emancipatory life vision, she wanted neither children nor adults to be limited more than necessary:

“I don't want to force anyone into anything and I don't want to be forced into anything.“

The social being determines consciousness

“...but I still believe that circumstances determine awareness. And if a child lives in an environment where it has never learned to be emphatic, a book can not change that.“

Video „Im Gespräch: Christine Nöstlinger“, 03.02.2016

Children, being humans who depend on adults, are particularly affected by the social and economic circumstances in which they live.

“What comes to mind about childhood: children are the most powerless class in the world, children must suffer the darkest sides and weaknesses of the time in which they live most severely.“

Source: Manuscript "Kinder und Kulturverhalten"

The social being determines consciousness part 2

Christine always put the dark sides and weaknesses of the present in perspective. When asked whether children are better (or worse) off today, in comparison to 30 years ago, she answered:

“Nowadays, the gap between rich and poor is widening more and more in economic terms, as is the situation of children. There is a group of reasonably well-off, educated parents. Their kids are doing great. ... But then there are children who are really struggling. They have a lot of things though - twenty Barbie dolls - produced in China, and a personal TV in their bedroom. But, in the end, nobody cares about them.“

Source: Ich bin eine heitere Pessimistin, Kurier, 23.09.2013

Christine, however, did not condemn parents who don’t “care” about their children. Being able to “be concerned” also depends on ones economic situation, education and social environment.

“There is a big difference between how the supermarket cashier sees her children – she'll probably experience them as a burden and hindrance to her own life, even if she sincerely loves them and will do everything for them – and how some petty bourgeois (sees her children). They play the helicopter-mom, bringing their four-year-old children to Chinese classes and ballet dancing. ... Clearly, there is a huge difference between these two mothers and their ideas of motherhood.“

The social being determines reading

“I am in favour of telling children the truth as much as possible – in a language they can understand.“

Language was Christine’s most important tool. The language a child understands when reading has always been influenced by how much parents read themselves and whether they have time and patience for children and books. However, the opportunities children have to entertain themselves have changed over time, and in Christine’s opinion, this had partly altered children's imagination:

“I believe that in order to read, you need a different type of imagination than some children develop nowadays. […] There may be exceptions, but if they [the children] don't possess the fantasy to connect pictures to the words they read, then you can't teach a child to read. … If children, on the other hand, grow up only with pictures, and that may happen to children from educationally disadvantaged backgrounds, they can no longer connect pictures to the words they read. ... These children in particular have a tremendous amount of life experience, and when they read a book full of simple five-word sentences, which is something they are able to read, then these may not be the stories they are interested in.“

The social being determines reading part 2

Christine once stated that she could no longer understand young people who continuously stare at their smartphones while swiping up. This statement became heavily quoted in the media. However, she did not have a negative attitude towards today's young people. Rather, it was the observation that she, as an author, no longer possessed the capacity to describe our contemporary world as accurately as necessary.

“But they [books] should be written by younger people. And maybe one has to do it completely different today. This may then – if possible – happen on social networks and no longer on paper.“

Source: Meine Enkelin speit, wenn sie zur Schule muss, Tagesspiegel, 27.01.2013

“I think it has become urgently necessary to publish children's books where children with a migration background are the heroes. But I can't write them. Children always want to identify with the heroes, with their thoughts and feelings, these need to be explained in detail. I can't do that for a migrant child.“

Source: Ich wollte allerhand nicht sein, Standard, 01.10.2016

The commercialisation of literature

The fact that only few books with such characteristics exist, was – according to Christine – due to an increasing commercialisation of literature, as well as a decreasing interest to reflect about children’s literature and the tendency to publish mainly content that ensure selling.

“We need new children's books, they said [when Christine began to write], we need to educate children differently – or not at all. [...] Nobody cares about debates like these today. Today a good children's book is one that sells well.

[...] In the past, books awarded with a prize were bought by the public sector to fill up the libraries. But today there's no money for that anymore.”

Source: Christine Nöstlinger wehrt sich gegen Textänderungen, Kurier, 21.02.2013

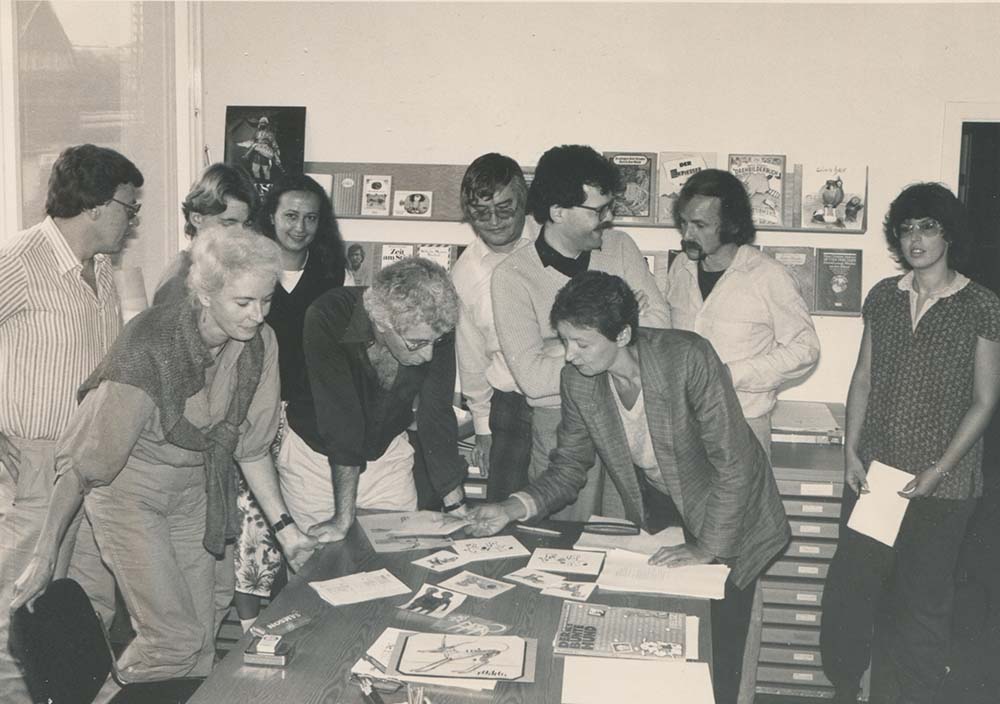

Photo: about 1977, Christine with publisher Hans-Jochen Gelberg and staff: Books were edited with care and in open discussion.

It’s not going to change anytime soon

Christine considered the commercialisation of children's and youth literature only as one aspect of a general social development, in which economic constraints restricted social and political activities in recent decades. Christine, as a political person, was observing these developments very narrowly and she did not like what she saw.

“I find it sad, that I can say with certainty, that in the remaining couple of years that I still have to live not much will change. I would have liked to have sunk into my grave satisfied, while thinking: This world is developing into something better, more beautiful and true. It would have been nice, but it's not like that.“

Source: „Hören S’ endlich auf damit!“

However, she never abandoned neither her enlightened attitude nor her practical commitment.

As a chairwoman of the human rights organisation “SOS Mitmensch” (1997–1999), for instance, she was committed to human rights in a world where justice, fairness and integration are possible.

But increasingly she felt that too little progress had been made on issues that were particularly important to her.

Education

Education was one of these particularly important themes for Christine. Education turns children into critical-thinking and empathic adults. As social institutions can compensate for the varying degrees of wellbeing among children, schools played an important role for her.

“But if you're for equal opportunities, you have to support integrated comprehensive schools, also by law. Of course, with the necessary money and know-how. To simply decide that we have such schools from now on, that's not enough.”

For Christine, the apparently much desired “freedom to chose ones level of education”, which would be lost through a legally regulated system of comprehensive schools, was an argument of those who did not want to provide equal opportunities at all.

“The children do not have the freedom of choice, their parents have a freedom of choice. And if I become excluded as a 10-year-old, I'm helpless.”

Source: Kinder, Schule, Kreisky, vida, 11.01.2011

As early as the 1970s, a fundamental school reform stipulating the base for an integrated and comprehensive school system in which children would no longer be differentiated and study together for eight years, were demanded as a prerequisite for equal opportunities. Christine stated 40 years later:

“I have the purest déjà vu. I feel like I am in the seventies again. The same debates, the same school experiments, the same conservative opponents, the same non-enforceability. I heard all of that forty years ago. I couldn’t have imagined to hear that again 40 years later.“

Source: Ich bin eine heitere Pessimistin, Kurier, 23.09.2013

“I can only explain it to myself by realising that certain social classes who send their children to high school (‘Gymnasium’) – even if they need a lot of private tutoring to become eligible – do not want the children of the lower classes to become equal by giving them the same chances. Countries with equal opportunities to a wider extent have a comprehensive and integrated school system.“

Equal rights for women

Christine was a housewife and mother in a time when men could still decide whether their wives could work or not.

“Back then, there wasn't a family law reform in place. My husband could have forbidden me to work. His authorisation was needed. I knew a single mother. When she wanted to travel to Italy with her child, she had to go to the senior guardianship to get her child a passport. One did not want to entrust a child at that time to an unmarried woman without any supervision. One really can't say that the conditions were better back then.“

Source: Ein Buch braucht kein Happy End, kontrast.at, 13.07.2018

Christine involuntarily and unhappily spent a decade being a housewife and mother only, later she combined household and child care with her writing. She would describe the behaviour of “left and enlightened men” as follows:

“And most of the fathers during the late seventies and early eighties hardly played anything else than the 'nice uncle' at home and left the education of their offspring to their wives, whether they were working or not.

One of these nice uncles, my husband, explained me his 'distanced approach' by saying that he simply doesn't know how 'being a father' works. He just knows he doesn’t want to become the father he had. By doing nothing, one can't do anything wrong.

I didn't want to become the mother I had either and I also didn't know how 'being a mother' worked, but I didn't protest because in all the families I knew closely, women were responsible for their children.“

Source: Rede auf der internationalen Jugendbuchtagung, ca. 1980

Equal rights for women Part2

It was not until the 1970s, that family and criminal law reforms in Austria created legal conditions to promote equality between men and women. Johanna Dohnal, State Secretary from 1979 and Federal Minister for Women's Issues from 1990, consistently pursued policies to reach gender equality. At a ceremony in memory of Johanna Dohnal in 2010, Christine said the following:

“Johanna was certainly a stroke of luck for women in our country because, as it rarely happens, she was the right woman in the right place. She reached the optimum of what could have been achieved during the years of her political activity. But one could also say: she reached as much as one could take from the powerful men of that time. And the autonomous women's movements of the 1970s played a major role in taking a great deal from them – let us not forget that. They gave Johanna an additional tailwind.“

Source: Rede anlässlich von Johanna Dohnal (Ge-)denken, 2010

Equal rights for women Part3

In Christine's view, however, the power relations between men and women had changed very little since the 1990s:

“For twenty years now, on women’s day I’ve been hearing the same things, and nothing’s changed. I hear the pay gap between men and women is 21 percent. I hear it continues to be 17 percent after one stops working part-time. This means we are second last or third last in the EU, ahead of Estonia and some other country.”

Source: Girls are strong, matschbanana, 13.07.2017

“Women still have the greater burden to bear. I believe there is a certain backlash among women themselves. The younger generation of women believes that emancipation is no longer necessary because everything has already been achieved. However, they didn't achieve anything.“

Source: Ich möchte ewig leben, News, 13.10.2016

“Generations of women have grown up who no longer care about feminism.”

Source: Frauentag: Warum so viele Frauen Feminismus falsch verstehen, miss.at

And when asked about the reasons for that, she answered:

“Well, now one could very simply say: There are always people who prefer to align with the powerful instead of the powerless. And since men are still the most powerful in our society, one just chooses the side of men. Often it's total stupidity.“

Source: Christine Nöstlinger: "Ich war kein Mamakind", Kurier, 14.05.2017

Flight and Migration

Christine was – privately and publicly – involved in supporting refugees and people with a migration background. Together with Ursula Pasterk she was godmother of a young refugee, donated to organisations that work with refugees, and took over the patronage of relief actions.

In 2016, during the award ceremony of the Ute Bock Prize for Civil Courage, Christine held the laudation for Angelika Schwarzmann, who had received the award for the successful resistance against the deportation of Syrian refugees to Hungary. In 2017, she donated a personal dialect poem to an auction in support of Hemayat, a care centre for torture and war survivors.

Within the scope of her possibilities, Christine wanted to act against xenophobia.

“It is statistically proven that xenophobia is most apparent where foreigners are least present. In the Eastern German federations, for example, foreigners make up less than 2% of the population. No need for real fears! [...] I suspect that people nowadays have many other fears which they connect to refugees.“

Source: Keiner hat das Recht zu gehorchen, Kleine Zeitung, 13. 07. 2018

She explained the mainstreaming of public resentments towards refugees and people with a migration background – which became more and more accepted after the “refugee crisis” of 2015 – as follows:

“That's incredibly sad, but: Whenever times get worse, people tend to become more right-wing oriented and not left. I can’t change that, that's how it is [...] Because life is quite complicated and for many people it lacks transparency. And because, in these times, people tend to resort to the simplest slogans and solutions. I have a friend who is a probation officer, who cares for citizens who have not worked a day in their life. And they scold foreigners and say, 'They'll take our work away from us.' When she answers, 'You fool, have you ever worked before?', he responds: 'No, but if they weren’t here, I would be working.'“

Source: Die Linken haben das nicht geschafft, progress, 13.07.2012

“It certainly has something to do with turbo-capitalism, that people feel left behind, that they can no longer connect to the current reality, and therefore they look for someone who can offer them simple solutions, even if they are the wrong ones.“

Source: Keiner hat das Recht zu gehorchen, Kleine Zeitung, 13.07.2018

While getting older, Christine could still be surprised by how people think and argument:

“From 1970 onwards, the lower middle class has progressed. For the last five years, however, their conditions are no longer increasing. But the lack of empathy for people who even have less, surprises me a lot.“

Source: Keiner hat das Recht zu gehorchen, Kleine Zeitung, 13.07.2018

She was even more shocked by migration politics in the year 2018:

“I can get extremely angry when it’s about refugees. Our chancellor stands up and states we must help them in the places they come from. And Austria is one of the countries that pays the least UN development aid. And he knows that. Every year, the UN Refugee Agency demands money from Austria. And we're not paying for it. Isn’t that lies and deceit?“

Source: Ein Buch braucht kein Happy End, kontrast.at, 13.07.2018

Although she was aware of the mechanisms that had contributed to the rise of right-wing popularity in recent years, there was no excuse for her:

“I often wonder how stupid one can be. I’m always asked to understand people's concerns. Usually these people do not inform themselves, they do not even watch the television news. So please, there is a certain civic duty towards society, you have to inform yourself.“

Source: Ein Buch braucht kein Happy End, kontrast.at, 13.07.2018

Christine was aware of her privileged life as one of the best-known children's book authors in the German-speaking countries. Therefore, she found it evident to help others. She realised that those, who were worse off, were less able to help. However, she found that not being able to help should be distinguished from rejection and xenophobia. The latter could neither be explained by economic circumstances nor by a lack of education:

“People are not coping with such miserable conditions, that one could explain it (xenophobia) by the circumstances they live in. One could name a hundred of reasons, but I’m slowly starting to think that it's always been inside people, however, now they can articulate it more easily. It takes time to write a letter to an editor. On the internet, all you need are your two fat sausages fingers.“

Source: Kinder wären arm, wenn sie nur meine Bücher hätten, Tiroler Tageszeitung, 28.09.2016

Socialist since day one

Having grown up in a socialist family, Christine criticised contemporary the Social Democrats for accepting the growing social inequalities and for adopting even right wing discourses.

“Well, the average Strache-voter in Vienna isn't that different from the average SPÖ-voter. That's why the red party behaves the way they do. But that's not a solution [….]“

Question: Do you understand social democratic leaders today, when howling with the right-wing wolves?

“No, I don't sympathise with that. I mean, it's ridiculous, there's this old saying: One doesn’t go to a blacksmith’s student, when one can go to the blacksmith directly. Everything the SPÖ adapts to, the FPÖ already masters.“

Question: So, the SPÖ should move to the left?

“Yes, that would be nice.“

Source: Die Linken haben das nicht geschafft, progress, 13.07.2012

Despite her criticism, Christine always remained loyal to the Social Democrats. She never became a SPÖ member, but always voted for the party and was a member of several committees supporting Social Democratic candidates.

The “Cloth of Civilisation”

Christine often compared the spirit of the seventies with the current zeitgeist and she observed how society has become more illiberal and undemocratic recently. She found the growing support for authoritarian and reactionary parties horrible.

“They (right-wing parties) take away my freedom, they take away from me the ideal of equal opportunities for all. And I don't like them because they all tend towards fascism.“

Source: Keiner hat das Recht zu gehorchen, Kleine Zeitung, 13.07.2018

The ‘Cloth of Civilisation’ Part2

“For me it is simply unbelievable, that members of radical right fraternities nowadays hold positions in all of our ministries, as well as other high offices. We know their policies and behaviour. It is all public. They're everywhere now. Even if this government is no longer in power after the next elections, these people will be there. Only through their retirement we can get rid of them. That can't be changed easily.“

Source: Ein Buch braucht kein Happy End, kontrast.at, 13.07.2018

She identified parallels to the interwar period, when corporative state dictatorship and Austrofascism led up to the Nazi system.

“During Austrofascism, no one rebelled any longer. It was not democracy that lead up to the Nazi period. It hadn’t been so much different beforehand. There were no concentration camps in place, but democracy was death since ‘34, I suppose.“

Source: Ein Buch braucht kein Happy End, kontrast.at, 13.07.2018

EN The ‘Cloth of Civilisation’ Part3

Christine grew up in Austria under the Nazi dictatorship and therefore knew how easily people could become inhumane:

“When we talk about ’38. We also experienced the most outspoken Nazis in Austria. Proportionately speaking, a great amount of concentration camp supervisors were Austrian. The hatred of Jews in Austria was – at least – as prevalent as elsewhere.”

Source: Ein Buch braucht kein Happy End, kontrast.at, 13.07.2018

Christine saw a society based on democracy and solidarity as an achievement of civilisation, which one should cherish and nurture:

“I grew up in the Nazi era. I didn’t 'grow' ... but I lived during the Nazi era. I know how easily people can become angry and inhumane. Such a thing may happen overnight. This ’cloth of civilisation’ seems to be very fragile and easy to tear off. Who takes care of that cloth?”

Source: Ein Buch braucht kein Happy End, kontrast.at, 13.07.2018

During the last years of her life she could not observe that people would take care of civilisation, and that made her resign:

“I'm not angry, you can't be angry for all of your life. I was never an angry person. It’s more that I have given up. I'm sad. It’s not how I had imagined society to look like at the end of my life. When you’re young today, you can still hope it will be different one day.”

Source: Ein Buch braucht kein Happy End, kontrast.at, 13.07.2018

Commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Mauthausen concentration camp

On 5 May 2015, Christine was invited to speak at the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Mauthausen concentration camp in the Historical Chamber of the Austrian Parliament: a speech against racism and xenophobia.